Coming out of Config 2024, the “conference for people who build products” hosted by Figma, the conversation about AI and design has reached a new pitch.

While AI-assisted search and layer renaming drew cheers, designers are decidedly more mixed on the Make Designs feature — which generates high-fidelity UI from a simple prompt — and news that unless they opt out, Figma will begin training the feature on their work.

Reactions on social media have the energy of frogs just noticing the waters around them getting increasingly hot, trapped in the same pot writers and visual artists have been stewing in for a while. Is this the end of design as practiced by human beings? Are we, as designers, cooked?

A second wave of reactions loudly answer, “No,” with all the confidence of Google’s AI telling you to put glue on your pizza. AI is just a tool. Designers do more than generate pixels, and machine learning won’t make that obsolete. AI doomers are just whining when they should be adapting.

We seem to agree we are at an inflection point, but not on the size of the turn ahead of us or the direction in which it will leave us heading.

There are two options ahead of us, if you follow the wisdom of the crowd: our submission to our robot overlords can be panicked or cheering. However, if we expand our points of view beyond design and AI to the history of work and technology, we can see where we are now and where alternative paths may lie.

Where we’re heading

Personally, I think the shift ahead will be seismic, and I’m skeptical it will be for the better.

In general, I’m more critical of AI. The most influential models are built on IP theft. Its environmental costs are absurd. It amplifies the bias of its training data. It’s easy to abuse. And its being applied to problems that it is fundamentally ill-suited for.

But unlike the Web3 hype before it, I do find the technology legitimately impressive, and can see it being valuable in a number of contexts. Behind all the Wizard of Oz demos, there’s enough “there there” to ensure AI will continue to find its way into product roadmaps.

If AI is right and ready for the challenges to which it’s being applied — or if consumers even want it — at this point, is almost moot. If Twitter Blue, Google AMP, or the early-aughts pivot to video haven’t made it clear, middling, user-hostile ideas can be brought to life if enough influential people see dollar signs in them.

Whether this presents an existential threat to design depends on whether you think Theseus is sailing the same ship — or how much you think design as it exists today can be changed while remaining essentially the same. I don’t think AI is going to completely eradicate all design jobs, but it’s poised to fundamentally change the nature of design work.

Not all change is bad. Design may be something humans have practiced since the first wheel, but as a profession it’s relatively young. Whether our job titles or daily tasks change is not what worries me, it’s how.

How we build and adopt AI products will have lasting consequences for design as a profession and the people who practice it.

We need to have some sticky conversations about this now to avoid losing what’s special about design, being exploited as a workforce, and doing lasting damage to the larger world.

There may be no going back, but we can influence the path ahead.

Let’s cover Config

Config, as a hub of professional community for designers, could be an ideal space to have these conversations if its host was not so invested in one of their possible outcomes. Instead, Figma gave the spotlight to people behind Perplexity, Dot, and the Rabbit R1.

While introducing speakers from Humane, makers of the dismally received Ai Pin, Figma’s emcees told us: rough launch aside, “you have to admire what they’re trying to build.” Reader, you do not.

While talking about designing for AI, Henry Modisett of Perplexity, told the audience you have to adjust your expectations for AIs output — prone as it is to unpredictability, inaccuracy, misattribution, and hallucination. But at no point did he provide a satisfying answer to why we should adjust our expectations down for the current state of a technology being adopted voluntarily.

In the same talk, he demonstrated how easily plain language could be used to put a fun cowboy hat on a photo of Figma CEO Dylan Field — not pausing to reflect on whether it was right to make manipulating images of real people so easy.

The AI programming at Figma was all “how-to” and no “should we,” giving their vision of AI in design an air of inevitability that has emboldened AI optimists and driven everyone else to near despair.

But it doesn’t have to be like this.

Don’t let your take-away from Config be the inevitability of this vision of AI in design. Instead, let this event be an important reminder that not everyone working to build products shares the same values or is betting on the same horses when it comes to our shared future.

While Figma has carefully cultivated a close brand relationship with designers, its ambitions have always been larger and are coming into clearer focus. The three product priorities announced at Config are: reducing complexity, improving the developer experience, and AI.

In isolation, the features announced are impressive and attractively designed. Respect to the people who worked on them, but the design community is right to be wary of the strategy behind them.

Will these improve individual designers’ efficiency? Maybe. But the disconnect between workers’ productivity and their compensation has been growing for decades. Designers’ ability to do more with less — and teams’ ability to do more with fewer designers — is more valuable to executives than individual contributors. And that’s exactly who Figma is appealing to with their AI strategy.

Designers who assume they, their bosses, and Figma are all working toward the same shared future are bound for disappointment when that future arrives.

The hype is self-fulfilling

Seeing design in the larger context of work, its various players, and their unique perspectives and incentives is essential to understanding the very real risks AI presents to designers.

The risk is not that AI is so well-suited to the task of design that it will effectively replace every working designer. No, the fact that Figma had to pull the Make Designs feature after launch because it was plagiarizing Apple is proof that generative AI isn’t an equal swap for a human designer (yet).

Professors Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo identify hype as one of the main reasons companies adopt “so-so” technology that puts people out of work without contributing meaningfully to productivity or quality in exchange. Shifting costs to consumers and realizing minor gains also make the list.

Good design may lead to better outcomes for customers and longer-term prospects for the business; but stakeholders looking to make a quick and comfortable exit may not give those the same weight as a short-term valuation bump from cutting people costs and incorporating the hot new thing.

AI doesn’t need to deliver the same quality as a human designer for executives to see it as a viable replacement. If enough people in charge of headcount at your company believe they can replace designers with AI, they will try.

We’re not making it out the same

The context in which designers work, what they do, and where they are in their careers will influence how AI impacts them.

Author Jim Butcher wrote that if you’re being chased by a bear, “You don’t have to run faster than the bear to get away. You just have to run faster than the guy next to you.”

To see things from the bear’s perspective, AI doesn’t need to be as good as the best designer. There are plenty of people in the bottom 50th percentile to snack on.

Someone shouldn’t have to be exceptional in their field to have stability; but sadly, I expect the job pool for early-career designers, production designers, and others to continue getting tighter.

We can’t assume the people in jobs consumed by AI will simply move on to new roles created by the technology, especially when that AI is being created by people who don’t believe those jobs should exist.

It’s true, technological innovations can create new work — people who used to do automated tasks take on new responsibilities, new tasks need to be fulfilled to facilitate the automation, and sometimes whole new industries spring up to support the development and maintenance of the technology. But in their research, Acemoglu and Restrepo identified an increase in automation and a decrease in resulting new work over the last 30 years.

We can’t keep building “so-so” AI products and expect them to create good jobs.

Not all jobs that are created by AI will be as stable or well-compensated as the ones they replace. Today’s prompt engineers are yesteryear’s telephone operators. There will be a category of work supporting AI products — helping improve those products — until they can be operated without an intermediary.

While critics of AI are often accused of hating it just because it is new, the risks it poses are not unprecedented.

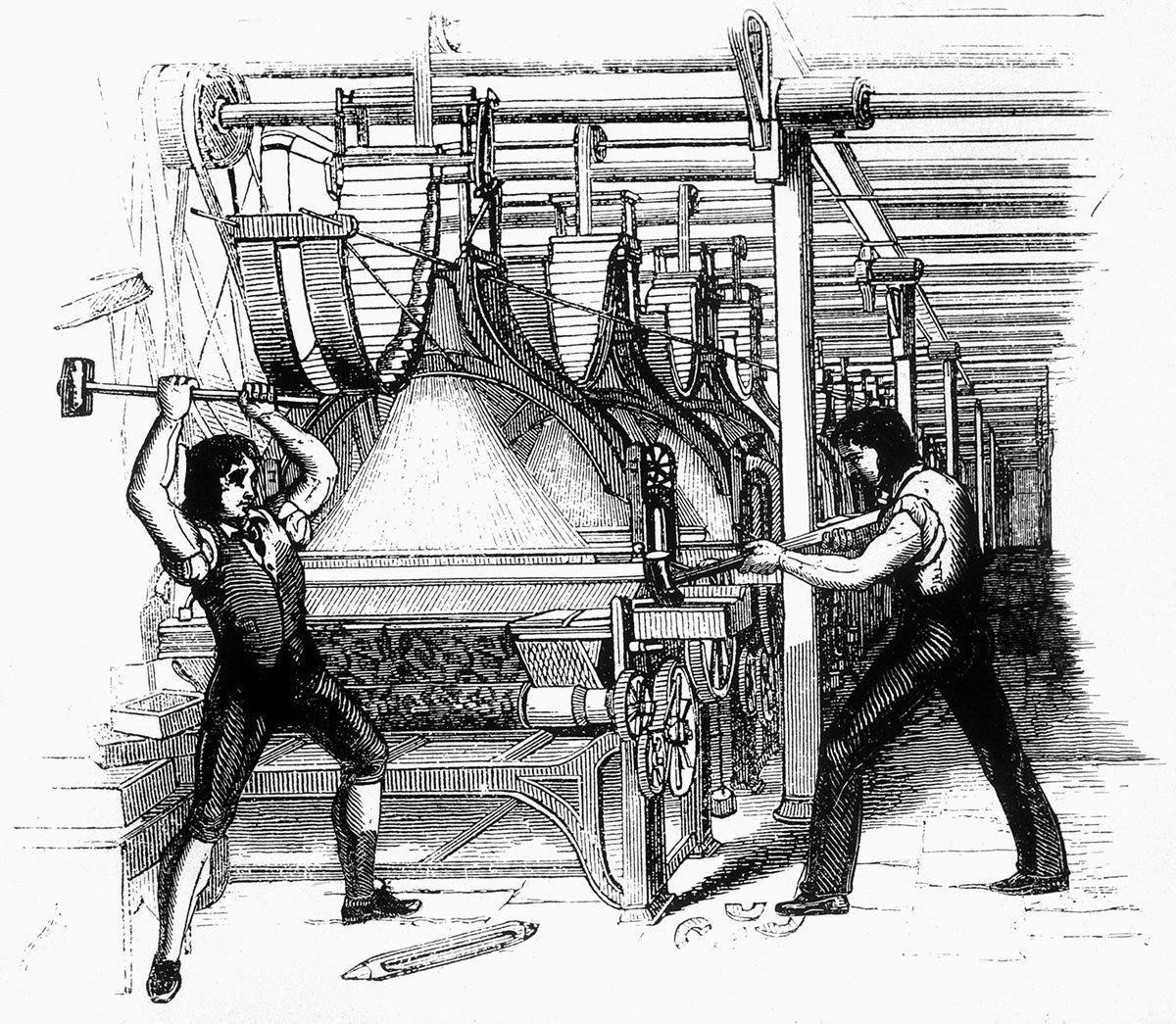

The Luddites were not offended by the novelty of automated industry. They protested factory owners using automation to replace workers and drive down wages with inferior goods produced at an inhuman scale.

Ursula Franklin’s The Real World of Technology captures “how much the technology of doing something defines the activity itself” in a way that feels as relevant to today as it does to the Industrial Revolution.

She notes how proponents of new technologies, “always stress the liberating attributes of a new technology, regardless of the specific technology in question,” even though the results are often less freeing.

Marketers of the sewing machine promised a world in which the people who were already sewing would be able to do it so efficiently, they’ll be able to clothe their communities. What they delivered is the movement of garment production from communities to sweatshops.

Throughout history, we see that when tasks are moved from people to capital, the benefits are not evenly distributed.

While Figma offers liberation from naming your layers, they’ll get much more from the AI they want to train on your work. Even that exchange is conditional on your continued subscription.

Figma is offering new tools, but we’re leasing them to replace tools we had more agency over.

The tool changes the task

To believe, uncritically, that AI is simply a new tool that will augment designers’ current capabilities is to willfully turn your back on the history of labor and new technologies.

Anything that changes the way we work also changes the work we do.

Some have likened AI Design tooling to the advent of Photoshop and its critics to studio designers clinging to X-acto knives and Letraset sheets to the very end. Others to the invention of photography. We still have painters, they argue, so designers should not be concerned about how their work will change.

But AI is not a camera, changing the way individuals capture an image. It’s a steam engine with the potential to reshape the way work is done at a global scale.

To quote Franklin again, the more technologies compartmentalize the work they’re grafted onto, the more they “eliminate the occasions for decision-making and judgment in general and especially for the making of principled decisions.”

An assembly line worker responsible for one step in a production process has less agency than a craftsperson working at human scale. That assembly worker also requires fewer skills.

There is real pressure to incorporate more and more AI in our work to establish proficiency in the industry’s hot new tool, but we can’t forget the trade-offs between learning and forgetting.

Any task we offload to AI, we risk losing ourselves. Consider some of the tasks designers have talked about outsourcing to AI tools: finding inspiration and concepting, copywriting, color palette creation, documentation, user research…

I’m not saying AI is never appropriate for any part of these tasks; but don’t let the real, valuable, and transferable skills we’d otherwise be using atrophy. In a world where you can generate v1 of a design at the click of a button, designers will need to be even more intentional about cultivating them.

Designers who assume their “taste and creativity” will be their killer differentiator from AI should remember that taste and creativity are muscles that must be exercised to stay strong. Many early career designers develop those muscles doing tasks now earmarked for AI.

The liberating promise of AI design tools is the end of doing such rote work. But who defines what work is rote, and what work remains valuable?

Introducing Figma’s AI tooling, Dylan Field asked the audience, “Who hasn’t faced a blank canvas before, and wondered how they could get through it,” before generating a high-fidelity web page in seconds.

The blank canvas is intimidating for sure; but it’s also an opportunity to consider what you are about to make, where you should start, and what belongs on the canvas at all. To skip ahead to decisions in reaction to an AI’s output is to sacrifice all of the possible insights, ideas, and small decisions the process of “getting started” engenders.

Designers’ true value is not in their ability to put pixels on a screen, but that is exactly what Figma’s vision of productivity values: filling the blank canvas more efficiently.

Field also acknowledges that AI, by its very nature, will generate obvious amalgamations of existing solutions. By increasing the relative cost of coming up with novel solutions (in time and salaries), AI tooling increases the value of standardization over innovation even more than the industry already has.

And what will we do when all our “rote work” is taken care of for us? Will designers then be free to tackle the bigger problems naming our layers has kept us from? Will our stakeholders finally see the value we can provide outside of putting pixels on a screen? Will we get a four-day work week to better enjoy the fruits of our ever-increasing productivity? Recent history does not suggest we will.

We may find that we’re kept busy enough cleaning up the output of AI features. As Figma begins training its AI on the designs we create using its AI, we should expect quality to collapse from meh to worse.Maybe this should be reassuring. Maybe lost jobs will come back to help businesses salvage what they’ve lost to automated enshittification. Hopefully we still remember how to do that.

The more deeply ingrained AI becomes in the design process, the harder it is to account for its costs, and the steepest of those costs are not born by designers.

No tool is neutral, and AI models have added biases, learned from their training materials. Biases that we ourselves may have trouble spotting in its output. Real people are not just excluded but also harmed by designs that are biased against them.

Whether we are designing AI products or just designing with them, accessibility and inclusion in design will continue suffer if we follow AI’s bent toward the status quo.

The cost of AI extends beyond the products we use it to build. The environmental impact of AI is immense, and we should really ask ourselves if the damage to our shared natural resources in a time of increasing climate disaster is worth the time we save renaming our layers.

The bottom line

At its heart, this is a conversation about cost and value. What does AI offer? What will it cost us? What is the true value of design? What do designers value?

When we talk about the cost and value of AI in design, we cannot forget the human beings who pay those costs and the human beings who are rewarded — and where those two groups diverge.

With this framing of cost and value, AI presents a final trap for designers: aligning our work exclusively to the bottom line.

Educating stakeholders about the business value of design seems to be the most trusted failsafe against AI job loss.

I truly believe educating stakeholders on design is a valuable and essential skill for designers; but to borrow a pointed metaphor from our environment, it’s equivalent to putting up sandbags after failing to make more structural change.

Not only will it fail to stop the tides from rising, it takes a lot of time and energy in and of itself. It’s not realistic or fair to expect designers to both meet the increasing productivity demands on their labor and also explicitly advocate for their continued employment. Especially when you consider the complexity and expense of measuring the impact of good design on the bottom line.

Being business aware as a designer means understanding that one of our most valuable contributions to business success is being able to connect the business’s goal to what people (users) actually want from our designs.

Users don’t care if we’re using AI nearly as much as the investor class does. We know who our employers are prioritizing, we can decide who we advocate for. We can’t do that if we cede all our ground to the bottom line. The bottom line as a compass will always point the conversation to dollars instead of people and orient it around quarters instead of lives.

We must also remember that while we’re talking about design as a function of a business, that’s not all design is. Design is a set of skills with a profound ability to shape the world inside and outside of business. The more we rely on human design as a “business differentiator,” the further and further design as a skillset will concentrate around luxury and mega-enterprise.

Working designers need to understand what our business partners value, we need to speak their language, we need to value their input, yes. But we can’t just become PMs. Designers need to offer our own unique perspectives to remain valuable.

The choice ahead

If we can’t trust the business value of design or our taste and creativity to spare us the worst possibilities, what can we trust? As cliché as it is, designers can trust ourselves and each other (mostly).

The risks inherent to AI do not uniquely affect designers, but we are unique in our proximity to the creation of many products powered by it. It’s unlikely the profession of design, as young as it is, remains unchanged by AI, but we can shape how.

Exercise agency in what tools you adopt. Shift your thinking from “minimum viable” to “minimum responsible” launches of the products you build.

This will be easier if designers exercise our collective power. Yes, this means unionization. But it also means creating spaces for these conversations that are not owned by private companies with a chokehold on our industry.

We’re people, we don’t have to be training content. Opt out of being used to better private machine learning models. Opt out of using products that don’t give you a choice.

When you do use AI, do it critically—eyes open to the inherent risks. Know your lines in the sand. What are your criteria for whether or not to use an AI product?

Our power isn’t limited to what we can exercise in our day jobs or as consumers, either. Support legislation that protects our data as individuals, our rights as labor, and our collective resources as communities.

We have more choices than obsolescence and acquiescence.

Adapting to AI doesn’t have to mean wholesale adoption and advocacy. Nor is it at odds with informed criticism.

The future of AI in design is not inevitable.

To end it with one more from Ursula Franklin:

The world of technology is the sum total of what people do. Its redemption can only come from changes in what people, individually and collectively, do or refrain from doing.